Two weeks ago I put forth my theory that the beauty of East Asian calligraphy lies in the balance it strikes between Vitality and Stability. Last week I provided examples of how a sense of Vitality is achieved, so this week we’ll conclude the thought with a discussion about Stability.

As with the previous entry, I’ll focus mainly on how Standard and Running Scripts (two of East Asian calligraphy’s five major branches) address the challenge of reconciling Stability and Vitality.

Achieving Stability

I previously described Stability as a quality encompassing these traits: form, order, balance, symmetry, consistency, predictability, sterility, objectivity, and sobriety.

Stability as I’m defining it usually isn’t evoked as a positive when discussing art; you probably wouldn’t describe artwork that you liked as being “consistent” or “predictable”. But Stability is a critical component of East Asian calligraphy (and most other art forms for that matter). In the very least, characters need to be legible*, which requires consistent, predictable ways of rendering their shapes and structures.

Beyond this most basic need, it is also generally believed that good calligraphy should be well-balanced & harmoniously composed, two qualities that fall under the canopy of Stability as I’m defining it.

Structural Integrity

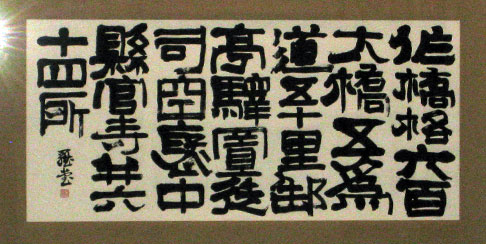

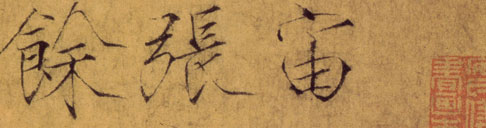

I didn’t really appreciate the structure of Chinese characters until I tried to recreate them myself. Below is a classic piece of calligraphy written in 653AD, and my own attempts at it:

I’ve picked a particularly dismal example of my own calligraphy (from shortly after I first started) to more clearly illustrate my point. But even now, my best efforts pale in comparison to what I’m modeling them after. My work is legible; any Chinese or Japanese person could read it. But it just doesn’t come together as a cohesive whole in the way that great calligraphy does.

The characters in the best calligraphic works appear to be structurally sound, like they could be used as the foundation of a building. That this internal stability is achieved using only a handful of precarious, unbalanced movements (i.e. the energy records that are lines) is truly remarkable.

A detailed description of how this stability is achieved is beyond the scope of this entry, so I’ll just briefly touch on a couple techniques:

Give and Take

As the Chinese written language evolved, it sought to communicate more and more complex ideas and phenomena. Many of the new characters created were combinations of previously established characters. A good example of this is how multiple instances of the character for “tree” were used to form new characters to express “forest” and “woods”:

When the characters were joined to form new characters, they were almost never just squished together without alternation. Instead, as shown above, certain strokes in each character would be lengthened or shortened, in order to accommodate each other and create a more unified whole.

Modulated Strokes

I previously wrote the modulated strokes, or lines with dynamic, varying widths, were used to create a sense of Vitality in calligraphic works.

But this technique also plays a critical role in enhancing the Stability of a work. As I wrote last time, the horizontal lines of characters written in Standard and Running Scripts tend to rise from left to right, both to facilitate ease of writing as well as to create a sense of imbalance which suggests movement:

It would at first blush seem impossible to reconcile Stability with the imbalance created by the right-rising technique. Calligraphers use fatter strokes in key places of the character, in order to ground it and introduce a sense of Stability to it.

A good example of this can be found in the character for “heaven”, shown here in four different styles of Standard Script:

As you can see, the final stroke (the one that concludes in the lower right hand corner of each example) is significantly fatter than any of the others. This helps to ground and stabilize the right side of the character, which would otherwise appear skewed due to the right-rising horizontal lines.

Using these techniques, as well as countless others, calligraphers are able to have their cake and eat it too; to create characters that suggest both Vitality and Stability at the same time.

*****

I have a couple more things I’d like to write about East Asian calligraphy, but I’d like to take a little break from it. So the entries for the next week or two will be about something else. Stay tuned!

(*Regarding the “necessity” for legibility: actually, Grass Script is sometimes so chaotic that even calligraphy experts are unable to read it, and some avant-garde calligraphers create work that is truly inscrutable. But anyway…)